Translational Science Benefits

Summary

Type 1 Diabetes is one of the most common chronic medical conditions in children, and its prevalence is growing at an alarming rate, especially in underserved communities.1,2,3 Type 1 Diabetes is a condition where the cells responsible for creating insulin are destroyed. Insulin is a hormone that is essential for the body to use glucose for energy; for this reason, people with Type 1 Diabetes have to take insulin injections. Controlling glucose manually with injections is an imperfect process. As a result, many kids have glucose levels that are outside of the recommended ranges. Unfortunately, when glucose is uncontrolled like this, it can lead to complications that affect the heart, brain, eyes, and kidneys.4 Barriers to controlling glucose levels make living with Type 1 Diabetes even more difficult. Eighty-one percent of youth report experiencing barriers that make glucose control harder, such as lack of social support, not having enough access to insulin, or not having access to healthy foods. These challenges are reported more often in youth from oppressed social groups.5

Although past studies highlight how common it is for youth to face challenges, most only asked about barriers one time using surveys or interviews in places like a doctor’s clinic or research laboratory. This “single snapshot” view could hurt our ability to understand the complexity of barriers to diabetes care and how those barriers impact glucose control, as patients may not be able to remember the challenges they faced when asked long after they occurred (e.g., 3 months later). Additionally, challenges might change throughout a single day making it difficult to understand which barriers affect glucose control the most. If we do not have a complete picture of what barriers youth from disadvantaged communities face in daily life and how they change, we cannot develop interventions to fully address them.

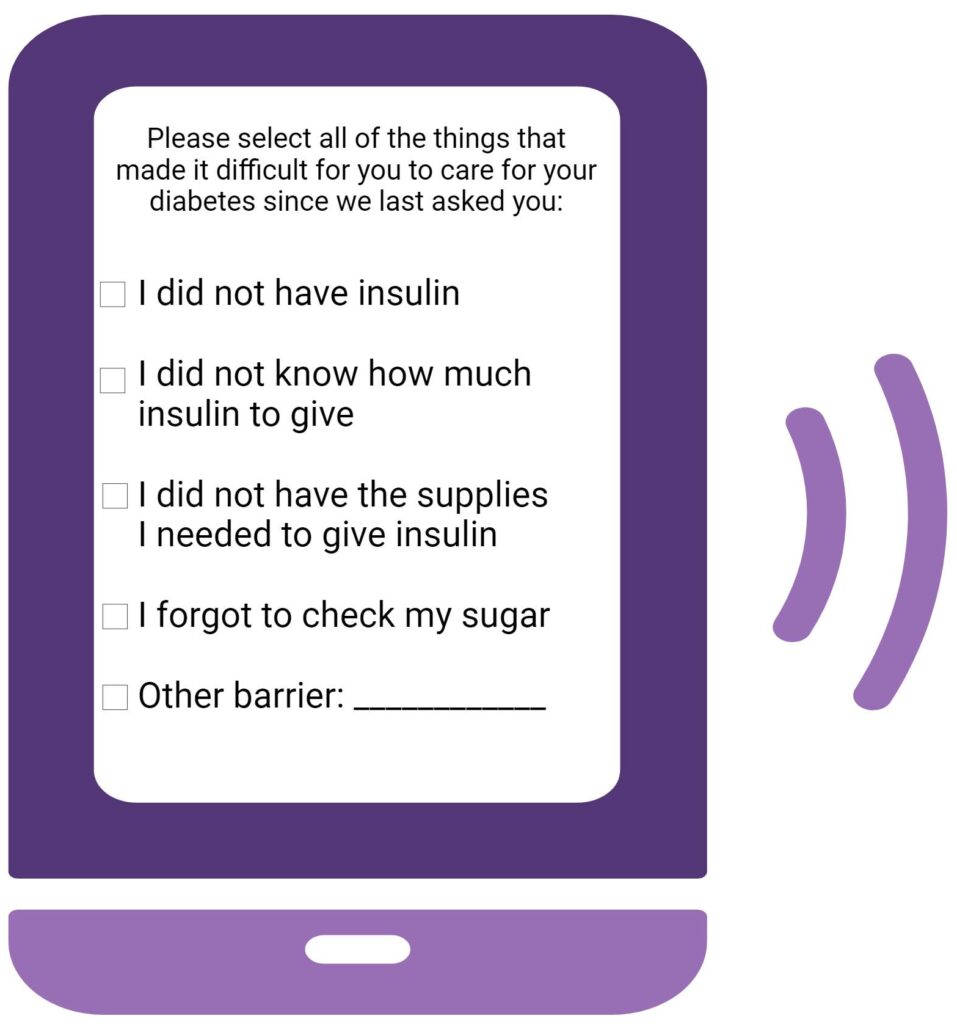

The purpose of Dr. Ray’s work is to better understand the challenges youth with Type 1 Diabetes experience in their day-to-day lives and how those challenges impact their ability to control blood glucose levels. To achieve this, the research team will use smartphone technology to ask youth about their barriers to diabetes care multiple times per day in real-time. Specifically, we will ask youth aged 9 to 16 to answer questions about the barriers they experience four times per day using a smartphone. Participants will also wear a continuous glucose monitor that will measure their glucose 288 times per day using a small sensor that goes under the skin. This information will be used to look at how short-term barriers to diabetes care affect glucose levels in the moment. This is the first step to understanding what barriers we should focus on when developing mobile technology interventions to help youth care for their diabetes.

Importantly, Dr. Ray and her team are conducting this work in collaboration with community outreach programs at Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital to reach youth from disadvantaged communities. These youth are often underrepresented in diabetes research and have less access to specialized diabetes care and include, youth from lower-income, Black and Latinx communities, and underserved rural communities.

Significance

This work is the first step needed to reach our long-term goal of developing and delivering individualized treatments for youth with Type 1 Diabetes via a smartphone app. The goal is for these treatments to help youth overcome barriers to diabetes care in the exact moment they face them in daily life. For example, if a child with diabetes reports not knowing how much insulin to take, the smartphone app we hope to develop could help them figure out their insulin dose in real-time. Ultimately, we hope these tools will help youth care for their diabetes and, therefore, reduce their chances of developing additional complications later in life from uncontrolled diabetes.

Our study will actively engage youth from three priority populations in health equity research that often have less access to specialized diabetes care: lower-income communities, Black and Latinx communities, and underserved rural communities. The long-term goal of this work is to inform the development of equitable, widely accessible individualized treatments designed to help youth overcome modifiable barriers to diabetes management in real-time. Importantly, we will continue to engage with youth who have diabetes and their parents to ensure the voices of those affected are part of our mission to improve health.

Benefits

Demonstrated benefits are those that have been observed and are verifiable.

Potential benefits are those logically expected with moderate to high confidence.

Clinical & medical benefits

The development of an individualized Type 1 Diabetes intervention using smartphone technology for youth from disadvantaged communities could help improve diabetes treatment and reduce the risk of associated medical complications. potential.

The development of an individualized Type 1 Diabetes intervention using smartphone software could help clinicians and patients better understand how barriers to diabetes care impact glucose levels. Further, this software could help youth better care for their diabetes by providing them with information and resources that allow them to quickly and effectively address barriers. potential.

Community & public health benefits

The development of an individualized Type 1 Diabetes intervention delivered through smartphone technology could help deliver specialized diabetes treatment in real-time to youth from disadvantaged communities who often have less access to such care. potential.

The smartphone app that we hope to develop would deliver individualized health education that could help improve glucose control and overall health in youth with diabetes. potential.

The development of smartphone technology could help make individualized treatment for youth from disadvantaged communities more accessible than traditional in-person clinic visits for diabetes care. potential.

The development of smartphone technology could allow us to deliver individualized treatment to youth from disadvantaged communities in real-time which is not possible through traditional in-person clinic visits for diabetes care. potential.

Better accessibility to individualized Type 1 Diabetes care would potentially reduce the risk of life-threatening medical complications of diabetes that often negatively affect quality of life. potential.

Economic benefits

Better access to individualized Type 1 Diabetes care could potentially reduce the risk of life-threatening medical complications of diabetes that are often costly for the patient, their family, and society as a whole. potential.

Clinical

The ultimate goal of our work is to develop a smartphone app to deliver individualized care to youth with Type 1 Diabetes from disadvantaged communities that will help them overcome barriers to diabetes care in real-time. We hope this intervention will improve glucose control, reduce the risk of medical complications from diabetes, and improve quality of life. The current project is the first step to achieving this goal because it will allow us to better understand what barriers youth from disadvantaged communities face, how those barriers change, and how they affect blood glucose in daily life.

Community

A smartphone app could potentially increase accessibility to individualized Type 1 Diabetes care for youth from disadvantaged communities. Instead of waiting for an upcoming clinic visit when youth may be less likely to remember what made their diabetes care difficult, they could get help in real-time at the exact moment they are facing a barrier. Improving access to care in communities that often have less access to specialized diabetes care could potentially improve glucose control and reduce the risk of life-threatening medical complications of diabetes that often negatively impact quality of life.

Economic

Better access to individualized Type 1 Diabetes care through a smartphone app could potentially reduce the risk of life-threatening medical complications of diabetes that are often costly for the patient, their family, and society as a whole. Further, the smartphone app intervention will be developed to be very inexpensive or free so that it is accessible to youth with diverse economic backgrounds.

Lessons Learned

One of the most important factors in this work has been the voice of youth with Type 1 Diabetes and their parents. The experience of each person with Type 1 Diabetes is different; hearing about experiences from each child and their parents has given us more insight into what questions we should ask when we think about barriers that youth experience in daily life. As we develop tools for youth with Type 1 Diabetes to use when overcoming barriers, it will be essential to continue including the voices and expertise of the patients living with diabetes that we are trying to help with our research.

1. Allen PJ, Vessey JA. Primary Care of the Child with a Chronic Condition. 4th ed. Mosby; 2004.

2. Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, et al. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1419-1429. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610187

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes- stat-report.html. Retrieved on June 29, 2021.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Is Type 1 Diabetes? Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/what-is-type-1-diabetes.html. Retrieved on March 1, 2024.

5. Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, et al. Prevalence of and Disparities in Barriers to Care Experienced by Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164(6):1369-1375.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.035