Translational Science Benefits

Summary

The burden of childhood cancer falls mainly on low- and middle-income countries, where 90% of children with cancer live and survival rates are lower.1–3 Medical resources are often limited and insufficient in low- and middle-income countries.2,4 In high-income countries, 80% of children diagnosed with cancer will survive, compared to 20% in some low- and middle-income countries.2,5 Pediatric cancer patients also have a higher risk of deteriorating while hospitalized and developing acute health complications and critical illnesses.6 Delays in transferring patients to the intensive care unit (ICU) during critical illness can result in poor outcomes, including increased organ dysfunction, a longer stay in the ICU, and higher death rates.7–11 Finding ways to recognize deteriorating health earlier in pediatric cancer patients may help improve survival. Reducing ICU stays can also ease the burden on hospitals in resource-limited settings.12

PEWS, or Pediatric Early Warning Scores, are clinical assessment tools used to detect deteriorating health early or even prevent deteriorating health in hospitalized children. Nurses routinely take patients’ vital signs and calculate a PEWS score that reflects changes in vital signs. Based on the score, nurses may alert other members of the healthcare team to take action. Implementing PEWS led to quicker administration of medical interventions, fewer hospital deaths, shorter hospital stays, and better communication across healthcare teams in hospitals in the United States.13,14 However, PEWS had not been widely used in resource-limited hospitals.

In an effort to improve outcomes for pediatric cancer patients in low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Asya Agulnik formed a team based at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and started Proyecto EVAT (“Proyecto” is Spanish for “Project” and EVAT stands for Escala de Valoración de Alerta Temprana). EVAT is the Spanish version of PEWS. The Proyecto EVAT team implemented EVAT PEWS at Unidad Nacional de Oncología Pediátrica (UNOP), a pediatric cancer center in Guatemala. The team found that scores on EVAT PEWS predicted deteriorating health and the need for ICU transfer for pediatric cancer patients in the resource-limited hospital.15 After EVAT PEWS implementation, UNOP had fewer pediatric cancer patients experience deteriorating health while in the hospital and fewer days spent in the pediatric ICU, as well as an estimated cost savings of $350,000.16

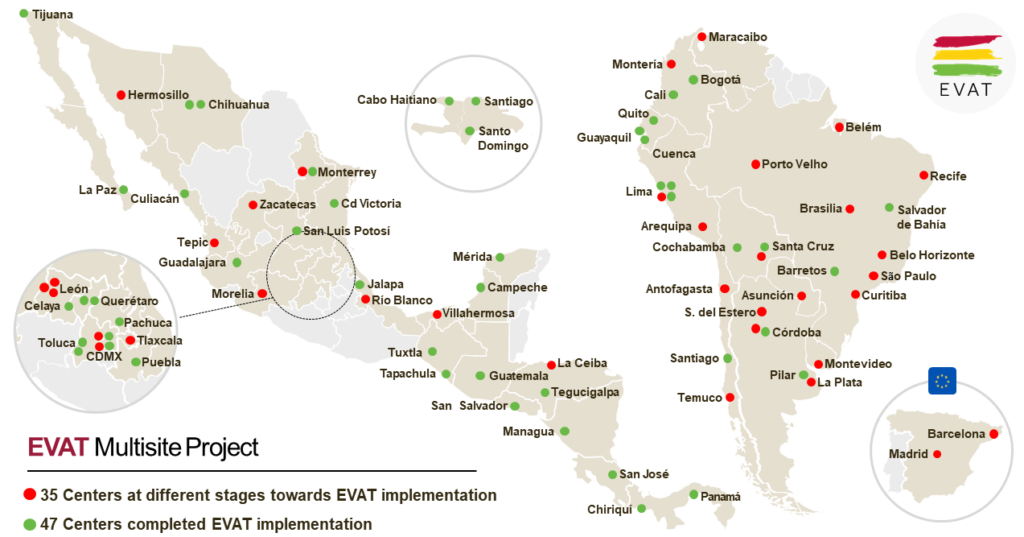

Building on the results of EVAT PEWS implementation at UNOP, Proyecto EVAT evolved into a quality-improvement collaborative with partners across Latin America. Cohorts of pediatric cancer centers join each year to implement EVAT PEWS. Centers that implemented EVAT PEWS in earlier years serve as regional mentors in the collaborative, providing EVAT PEWS training in Spanish as well as advice tailored based on each hospital’s resources.

Significance

Proyecto EVAT is improving the care and survival of pediatric cancer patients with the poorest projected outcomes and has already reached over 41,000 children. Proyecto EVAT focused on program sustainability from the start to ensure that the use of PEWS would continue long-term. Across 36 centers that implemented EVAT PEWS from April 2017 to October 2021, all 36 centers were still using EVAT PEWS for up to 18 months after initial implementation.17 Proyecto EVAT team members also developed a Spanish-language Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool (CSAT), used to assess a hospital’s capacity to sustain an intervention such as PEWS.18 Proyecto EVAT trained over 11,000 physicians and nurses and for many it was their first experience with a quality improvement project.17 With the CSAT tool and their training, healthcare teams are positioned to collaborate and implement future quality improvement initiatives.

After PEWS was successfully implemented in the pediatric cancer center in Guatemala, yearly cohorts of 10-14 medical centers were launched throughout Latin America. The EVAT PEWS network now includes a total of 80 centers across 20 countries, where it has been fully implemented in a total of 50 centers (as of July 2023). The Proyecto EVAT team is currently working on an adaptation of the implementation strategy that would allow implementation to expand to other regions globally, including Africa. This offshoot project is titled PASHA, or PEWS Adaptation to Support Hospitals in Africa.

Benefits

Demonstrated benefits are those that have been observed and are verifiable.

Potential benefits are those logically expected with moderate to high confidence.

EVAT PEWS is a diagnostic system to predict deteriorating health in hospitalized pediatric cancer patients.15 demonstrated.

Clinical

EVAT PEWS was implemented in 80 low-resource hospitals, allowing for earlier detection of deteriorating health in hospitalized children who would not otherwise have access to such care. demonstrated.

Community

Implementation of EVAT PEWS fostered interdisciplinary communication between front line staff members, mid-level managers, and executives,13,19 and also led nurses to feel empowered.19,20 demonstrated.

Community

Medical staff members reported EVAT PEWS as being a valuable tool for improving quality of care by allowing them to quickly redirect resources for the care of deteriorating patients to enhance recovery.21 demonstrated.

Community

EVAT PEWS led to perceived improvements in communication between providers and families and allowed families to better understand hospital care.22 demonstrated.

Community

Implementation of EVAT PEWS resulted in fewer deaths and shorter ICU stays for children with pediatric cancer who get sicker while in the hospital.23 demonstrated.

Community

Training on EVAT PEWS was incorporated into the medical student and pediatric resident curriculum at the Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon in Mexico.24 demonstrated.

Community

Training on EVAT PEWS was incorporated into nursing curriculum at the Universidad Estatal de Bolívar in Ecuador. demonstrated.

Community

Implementing EVAT PEWS resulted in yearly savings of up to 350,000 dollars.12 demonstrated.

Economic

By improving pediatric cancer outcomes, Proyecto EVAT could reduce the substantial economic cost of pediatric cancer on low- and middle-income countries. potential.

Economic

The Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, a public health system in Mexico, is integrating EVAT PEWS into their national health policies. potential.

Policy

The Ministry of Health in Peru will incorporate EVAT PEWS into nursing recommendations as part of their Cure All initiative.17 potential.

Policy

The regional ministry of health in Veracruz, Mexico is incorporating EVAT PEWS into their nursing care standards. potential.

Policy

This research has clinical, community, economic, and policy implications. The framework for these implications was derived from the Translational Science Benefits Model created by the Institute of Clinical & Translational Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.25

Clinical

Proyecto EVAT created a new diagnostic system, EVAT PEWS, which can predict deteriorating health in hospitalized pediatric cancer patients, allowing medical staff to respond quickly when a patient’s condition is deteriorating.15 A multidisciplinary team created EVAT PEWS by translating an existing tool into Spanish and modifying the tool to the local healthcare practices. The team’s research confirmed the link between EVAT PEWS scores, and severity of illness and death in a resource-limited hospital.15

Community

By implementing EVAT PEWS, medical staff are able to more quickly identify deteriorating health in pediatric cancer patients and direct resources to these patients. This has increased the quality of critical care for children with cancer.26 This system has been used in 80 low-resource hospitals, with more added each year, increasing access to better clinical care for pediatric patients who would otherwise not have access to the same level of care. Implementing EVAT PEWS has also improved outcomes for pediatric cancer patients. When EVAT PEWS was implemented in resource-limited hospitals, fewer pediatric cancer patients got sicker while in the hospital.16 Implementation of EVAT PEWS has also improved life expectancy by lowering death rates during health deterioration by as much as 18% across multiple centers, with centers that had a higher baseline mortality experiencing the greatest benefit.23

Medical staff also reported that implementation led to perceived improvements in communication between staff and families, which could lead to better relationships between staff and families, and also help families better understand the process of care.22 Team members conducted interviews with 41 medical staff members at UNOP, the pediatric cancer center in Guatemala, and 42 medical staff members at St. Jude. These interviews revealed that implementation of EVAT PEWS fostered interdisciplinary communication between medical staff and also empowered nurses and beside providers.13,20 Regardless of resource levels, medical staff members at both facilities saw EVAT PEWS as a valuable tool for improving quality of care.21 Additional interviews of physicians, nurses, and administrators at 5 resource-limited medical centers in Latin America found similar results, and also found that implementing EVAT PEWS led to a perceived reduction in negative patient events.19

Training on EVAT PEWS was incorporated into the medical educational curriculum at the Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon in Mexico.23 Additionally, in Cuenca, Ecuador, training on EVAT PEWS is now part of the educational curricula required for all aspiring nurses at the Universidad Estatal de Bolívar.

Economic

At UNOP, the pediatric cancer center in Guatemala, implementing EVAT PEWS saved $350,000 in one year.12 This cost savings resulted mainly from reducing the length of ICU stays for pediatric cancer patients who had experienced deteriorating health while in the hospital, as well as allowing hospital teams to redirect human resources promptly for the care of deteriorating patients in earlier stages of deterioration.12 By improving pediatric cancer outcomes, Proyecto EVAT can reduce health care costs and patient costs, and therefore may reduce the substantial economic cost of pediatric cancer on low- and middle-income countries.

Policy

The Hospital de Pediatria del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI is a cancer center in Mexico that is part of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, one of several public health systems in Mexico. After the Hospital de Pediatria del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI joined the Proyecto EVAT multisite project, the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social created a centralized coordinating office to track pediatric cancer outcomes. The Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social is now working to integrate EVAT PEWS into their national health policies.

EVAT PEWS are being incorporated into health care standards. In 2018, the World Health Organization and St. Jude launched the Cure All initiative with the goal of improving outcomes for children with cancer around the globe. After leading cancer centers in Peru independently joined Proyecto EVAT and successfully implemented EVAT PEWS, the Ministry of Health in Peru decided to incorporate EVAT PEWS into nursing recommendations as part of the Cure All initiative. Additionally, in Veracruz, Mexico, the regional ministry of health is incorporating EVAT PEWS into their nursing care standards.

Lessons Learned

Critical to the success of Proyecto EVAT were the collaborative network, regional mentorship, and the ability of local clinical staff to adapt implementation of EVAT PEWS.17 Proyecto EVAT used a Train the Trainer method. Specifically, international PEWS experts trained local teams on standardized implementation methodology. The local teams then trained local clinical staff, allowing the clinical staff to adapt the system for their own facility. Proyecto EVAT also collected pre-implementation data which was used to guide hospitals in identifying problems in the care they provide for pediatric cancer patients. Proyecto EVAT demonstrated the feasibility of implementing EVAT PEWS in resource-limited medical settings on a large scale when proper methodology is used.17 The Proyecto EVAT team is now analyzing factors that are associated with sustainability after implementation to identify potential methods to enhance sustainability.

- Force LM, Abdollahpour I, Advani SM, et al. The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(9):1211-1225. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30339-0

- Bhakta N, Force LM, Allemani C, et al. Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(1):e42-e53. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30761-7

- Khan Sial GZ, Khan SJ. Pediatric Cancer Outcomes in an Intensive Care Unit in Pakistan. JGO. 2019;(5):1-5. doi:10.1200/JGO.18.00215

- Muttalib F, González-Dambrauskas S, Lee JH, et al. Pediatric Emergency and Critical Care Resources and Infrastructure in Resource-Limited Settings: A Multicountry Survey. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49(4):671-681. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004769

- Childhood and Adolescence Cancer – PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. Accessed February 14, 2023.

- Agulnik A, Cárdenas A, Carrillo AK, et al. Clinical and organizational risk factors for mortality during deterioration events among pediatric oncology patients in Latin America: A multicenter prospective cohort. Cancer. 2021;127(10):1668-1678. doi:10.1002/cncr.33411

- Churpek MM, Wendlandt B, Zadravecz FJ, Adhikari R, Winslow C, Edelson DP. Association between intensive care unit transfer delay and hospital mortality: A multicenter investigation. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2016;11(11):757-762. doi:10.1002/jhm.2630

- Sankey CB, McAvay G, Siner JM, Barsky CL, Chaudhry SI. “Deterioration to Door Time”: An Exploratory Analysis of Delays in Escalation of Care for Hospitalized Patients. J GEN INTERN MED. 2016;31(8):895-900. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3654-x

- Young MP, Gooder VJ, McBride K, James B, Fisher ES. Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit: Delays are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):77-83. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20441.x

- Cardoso LT, Grion CM, Matsuo T, et al. Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R28. doi:10.1186/cc9975

- Demaret P, Pettersen G, Hubert P, Teira P, Emeriaud G. The critically-ill pediatric hemato-oncology patient: epidemiology, management, and strategy of transfer to the pediatric intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):14. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-2-14

- Agulnik A, Antillon‐Klussmann F, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, et al. Cost‐benefit analysis of implementing a pediatric early warning system at a pediatric oncology hospital in a low‐middle income country. Cancer. 2019;125(22):4052-4058. doi:10.1002/cncr.32436

- Graetz D, Kaye EC, Garza M, et al. Qualitative Study of Pediatric Early Warning Systems’ Impact on Interdisciplinary Communication in Two Pediatric Oncology Hospitals With Varying Resources. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;(6):1079-1086. doi:10.1200/GO.20.00163

- Sefton G, McGrath C, Tume L, Lane S, Lisboa PJG, Carrol ED. What impact did a Paediatric Early Warning system have on emergency admissions to the paediatric intensive care unit? An observational cohort study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2015;31(2):91-99. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2014.01.001

- Agulnik A, Méndez Aceituno A, Mora Robles LN, et al. Validation of a pediatric early warning system for hospitalized pediatric oncology patients in a resource‐limited setting. Cancer. 2017;123(24):4903-4913. doi:10.1002/cncr.30951

- Agulnik A, Mora Robles LN, Forbes PW, et al. Improved outcomes after successful implementation of a pediatric early warning system (PEWS) in a resource-limited pediatric oncology hospital: Improved Outcomes Using PEWS in Guatemala. Cancer. 2017;123(15):2965-2974. doi:10.1002/cncr.30664

- Agulnik A, Gonzalez Ruiz A, Muniz‐Talavera H, et al. Model for regional collaboration: Successful strategy to implement a pediatric early warning system in 36 pediatric oncology centers in Latin America. Cancer. 2022;128(22):4004-4016. doi:10.1002/cncr.34427

- Agulnik A, Malone S, Puerto-Torres M, et al. Reliability and validity of a Spanish-language measure assessing clinical capacity to sustain Paediatric Early Warning Systems (PEWS) in resource-limited hospitals. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e053116. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053116

- Mirochnick E, Graetz DE, Ferrara G, et al. Multilevel impacts of a pediatric early warning system in resource-limited pediatric oncology hospitals. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1018224. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.1018224

- Graetz DE, Giannars E, Kaye EC, et al. Clinician Emotions Surrounding Pediatric Oncology Patient Deterioration. Front Oncol. 2021;11:626457. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.626457

- Garza M, Graetz DE, Kaye EC, et al. Impact of PEWS on Perceived Quality of Care During Deterioration in Children With Cancer Hospitalized in Different Resource-Settings. Front Oncol. 2021;11:660051. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.660051

- Gillipelli SR, Kaye EC, Garza M, et al. Pediatric Early Warning Systems (PEWS) improve provider‐family communication from the provider perspective in pediatric cancer patients experiencing clinical deterioration. Cancer Medicine. Published online September 21, 2022. doi:10.1002/cam4.5210

- Agulnik A, Muniz-Talavera H, Pham LTD, et al. Effect of paediatric early warning systems (PEWS) implementation on clinical deterioration event mortality among children with cancer in resource-limited hospitals in Latin America: a prospective, multicentre cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. Published online July 2023:S1470204523002851. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00285-1

- Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon. Capacitacion de MIPs EVAT HU. Presented at: September 4, 2020.

- Institute of Clinical & Translational Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. Translational Science Benefits Model website. Published February 1, 2019.

- MINSAL recognizes the best practices in quality. Ministerio de Salud. Published December 12, 2019.