Translational Science Benefits

Summary

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide.1 One in five Veterans have depression.2 Affecting more than a million Veterans nationwide, depression is only less common than hypertension, diabetes, and low back pain.3 Most Veterans with depression are first identified in primary care, including many who are reluctant to consult mental health specialists. However, only half of Veterans with positive depression screens initiate any effective treatment, including either psychotherapy (such as cognitive behavioral therapy) or anti-depressant medication.4,5 Collaborative care models, where nurse care managers, mental health specialists, and primary care providers work together to treat depression within primary care,6,7 have enabled specialists to support primary care providers in prescribing medication. Yet, psychotherapy works as well as medication, has longer-lasting effects,8 and is preferred by Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) primary care patients.9 Despite this, timely and sufficient access to psychotherapy has remained unattainable.10–12

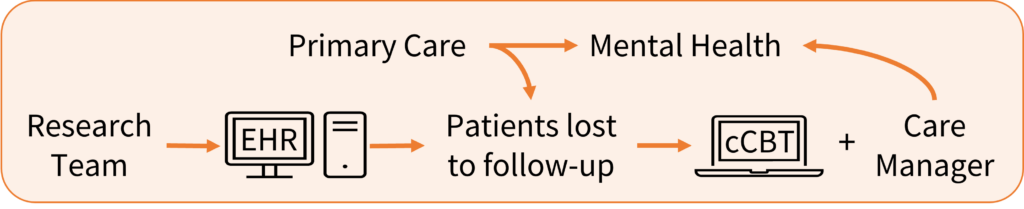

We adapted a pre-existing depression collaborative care model to improve patient reach, increase clinic and provider adoption, and broadly facilitate computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (cCBT) implementation in VA primary care clinics in the greater Los Angeles area. To develop this enhanced collaborative care model, we interviewed primary care and mental health care providers, as well as Veterans. They provided feedback on the acceptability of integrating cCBT into primary care and suggestions on how best to do so. We also worked with Veteran volunteers to co-design our adapted care model and the web-based cCBT program used in the study. A pilot randomized control trial was then conducted to test our cCBT-enhanced collaborative care model. We recruited participants with depressive symptoms and randomized them to receive either cCBT-enhanced collaborative care or usual care (see Figure 1).

Usual care typically includes prescription medication and follow-up with a nurse care manager. cCBT-enhanced collaborative care included commercially available cCBT program and 6 virtual sessions with a care manager, who promoted and monitored cCBT use (see Figure 2).

For this study, we partnered with Prevail Health to adapt their web-based cCBT program, Vets PrevailTM. Vets PrevailTM includes 12 self-paced lessons, access to Veteran peers for support, and program tailoring (through personalized program features and responsive text/audio). Self-reported assessments were completed just before participants began cCBT and after 3 months. They contained questions about demographics, health services and medication use, depressive symptoms, quality of life, and activation (i.e., knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage health).

Significance

Results from our pilot randomized control trial indicate cCBT-enhanced collaborative care is feasible, acceptable, and possibly effective in treating primary care patients with depression. Participants completed the majority of cCBT lessons (mean 6.7 out of 11) and rated them highly. They also liked the format of the program. One participant reported, “I liked the videos, they were detailed. They were quick and easy to get into.” Participants found the interaction with the care manager helpful. “I liked the interaction because it held me accountable,” said another participant. Additionally, among those who completed the study, 4 (19%) in the intervention group achieved partial or full remission over 3 months compared to 1 (5%) in the control group. While the pilot trial has concluded, we assembled necessary materials (e.g., provider- and patient-facing instructions) and leveraged informatics (e.g., electronic health record note templates and flags) to sustain local implementation. cCBT-enhanced collaborative care has now been adopted by VA Los Angeles clinics and continues to be available to the Veterans they serve. By engaging more Veterans in depression treatment, we aim to lower downstream suicide risk, especially among Veterans who may not otherwise engage in traditional mental health treatment but are open to non-stigmatizing internet-based psychotherapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first US-based clinical trial to examine the effectiveness and implementation of collaborative care models enhanced with clinician-supported cCBT to treat Veterans with depression in primary care. Additionally, the enhanced collaborative care in this study was developed in collaboration with Veterans which meant the model was tailored for their needs and preferences. Given its pragmatic study design and recruitment strategies (e.g., few exclusion criteria), our study participants represented a diverse VA patient sample (e.g., 30% women, 26% Black, 32% Hispanic, 21% homeless-experienced). If successful, cCBT can be readily incorporated into existing collaborative care models and disseminated nationally across all VA primary care clinics. The knowledge gained from our work will allow the VA to disseminate care models that leverage cCBT for depression and other psychiatric illnesses among primary care populations more effectively, efficiently, and rapidly. Adapting VAʼs collaborative care models to incorporate cCBT with human support can improve availability and access (via telehealth) to psychotherapy, which is often the preferred depression treatment modality among racial-ethnic minority patients.

Benefits

Demonstrated benefits are those that have been observed and are verifiable.

Potential benefits are those logically expected with moderate to high confidence.

Provided valuable feedback to partners developing the cCBT software on content, tailoring, and communication within the program (e.g., video visits with the care manager). Supported a diverse group of Veteran patients to successfully use a computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy program. demonstrated.

Clinical

Developed a new method of delivering clinician-supported computerized CBT into existing primary care services that requires minimal clinician support and time. demonstrated.

Clinical

Increased access to psychotherapy for Veterans for those who may be reluctant to engage in care, prefer telehealth, or live in rural areas. demonstrated.

Community

Developed an intervention that provides a new method of delivering psychotherapy to Veteran patients that is feasible and acceptable. demonstrated.

Community

Provided a timely alternative for psychotherapy and reduced depressive symptoms. potential.

Community

Created potential cost savings for the healthcare system by reducing the need for highly skilled psychotherapists. potential.

Economic

Reduced the rate of depression among Veterans, which could reduce costs associated with prolonged depression treatment, workplace costs including missed work days, and suicide-related costs. potential.

Economic

Developed research reports and a delivery guide to implement cCBT enhanced collaborative care. demonstrated.

Policy

Support VA program offices in the development of policies for effective implementation of cCBT enhanced collaborative care. potential.

Policy

This research has clinical, community, economic, and policy implications. The framework for these implications was derived from the Translational Science Benefits Model created by the Institute of Clinical & Translational Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.13

Clinical

cCBT can bridge large gaps in psychotherapy access for veterans who commonly experience depression, which when untreated may lead to serious disability. Depression treatment is still limited chiefly to medication, while traditional psychotherapy (e.g., CBT) remains largely inaccessible in the VA. Expanding depression treatment options available directly in primary care via cCBT-enhanced collaborative care may overcome mental health care access challenges for veterans who are disproportionately affected by psychiatric disease and suicidality.

Community

If successfully implemented, cCBT can be readily incorporated into existing depression collaborative care models and disseminated nationally. Greater engagement in depression treatment via cCBT uptake may reduce depressive symptoms and downstream suicide risk for many Veterans (e.g., working Veterans who seek convenient care and Veterans living in rural areas without nearby access to mental health care).

Economic

cCBT studies on cost-effectiveness and savings are promising.14,15 Internet-based cCBT can be completed asynchronous to clinical appointments and at the comfort of a patientʼs home computer or mobile device, with potential to overcome transportation or work-related barriers to medical care. Compared to face-to-face CBT, cCBT has been shown to be non-inferior when supported by clinicians, and it requires an average of 8-times less therapist time.16 Additionally, the societal cost of depression is large, encompassing cost of treatment, suicide-related costs, and missed workdays. Increasing accessibility of depression treatment through cCBT can reduce depressive symptoms and reduce the societal cost of depression.

Policy

Though cCBT was offered nationally to all Veterans, there was limited uptake among Veterans and clinicians. Few Veterans utilized and completed cCBT for depression; clinicians reported not knowing cCBT was available, or how to offer it as a treatment option. cCBT-enhanced collaborative care models within primary care were tested and implemented in one VA healthcare system with substantial multilevel stakeholder guidance (e.g., leaders, clinicians, and patients). The scientific reports, implementation materials, and informatics tools produced as part of our study were developed in collaboration with VA operational partners; they are intended to aid in policy and practice, whereby VA Clinical Practice Guideline recommended cCBT may be more readily delivered nationally via preexisting collaborative care models.

Lessons Learned

Collaborative care models can be feasibly enhanced with cCBT, which was acceptable to VA patients and providers and possibly effective in more greatly engaging Veterans in depression treatment. Partnering with Veterans and clinicians to develop the enhanced collaborative care model and adapting the cCBT software allowed us to create a more tailored experience from the outset, be more prepared for potential pitfalls during trial, and respond appropriately. Given the pilot nature of this research, a future hybrid effectiveness-implementation study is needed to confirm preliminary findings. This study is also limited to its focus on VA Los Angeles where the clinical complexity of Veterans is higher than average. For example, Los Angeles serves many Veterans experiencing homelessness who have socioeconomic problems and functional barriers to technology use.

- Depressive disorder (depression). Accessed April 29, 2024.

- Yano EM, Haskell S, Hayes P. Delivery of gender-sensitive comprehensive primary care to women veterans: implications for VA patient aligned care teams. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 2):703-707.

- Yoon J, Chow A. Comparing chronic condition rates using ICD-9 and ICD-10 in VA patients FY2014–2016. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17.

- Szymanski BR, Bohnert KM, Zivin K, McCarthy JF. Integrated Care: Treatment Initiation Following Positive Depression Screens. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):346.

- Levine DS, McCarthy JF, Cornwell B, Brockmann L, Pfeiffer PN. Primary Care–Mental Health Integration in the VA Health System: Associations Between Provider Staffing and Quality of Depression Care. Psychiatr Serv. Published online January 3, 2017.

- Ep P, M M, P D, L L. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health J Collab Fam Healthc. 2010;28(2).

- Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center – Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences. Accessed April 29, 2024.

- Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Kansagara D, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic Versus Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):350-359.

- Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2005;30(2):164-173

- Farmer MM, Rubenstein LV, Sherbourne CD, et al. Depression Quality of Care: Measuring Quality over Time Using VA Electronic Medical Record Data. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(Suppl 1):36-45.

- Leung LB, Escarce JJ, Yoon J, Sugar CA, Wells KB, Rubenstein LV. High Quality of Care Persists Despite Shifting Depression Services from VA Specialty to Primary Care. Society of General Internal Medicine; April 11-14, 2018, 2018; Denver, CO.

- Js F, De S, Ak L, A R, Sa M, B N. Behavioral health interventions being implemented in a VA primary care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18(1).

- Institute of Clinical & Translational Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. Translational Science Benefits Model website. Published February 1, 2019. https://translationalsciencebenefits.wustl.edu/

- Mitchell LM, Joshi U, Patel V, Lu C, Naslund JA. Economic Evaluations of Internet-Based Psychological Interventions for Anxiety Disorders and Depression: A Systematic Review. J Affect Disord. 2021;284:157.

- Thase ME, McCrone P, Barrett MS, et al. Improving Cost-effectiveness and Access to Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Depression: Providing Remote-Ready, Computer-Assisted Psychotherapy in Times of Crisis and Beyond. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(5):307.

- Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):329-342.